Trout rise in many different ways. The behavior of surface feeding salmonids is dictated by a number of variables. The type and volume of insects is one important factor. Mayfly rises are typically more like gulps or sips. Caddis rises are often splashy. When trout are taking hopping or skating stoneflies, it’s more like an explosion than a rise. Large insect volumes sometimes mean fish slow their rise forms; the slurry of food drifting past them means any time they choose to surface they are likely to intercept an insect. Current speed is another factor. Rises in fast current are, as one would guess, faster and appear more aggressive than rises in slow or moderate current. Today, however, the factor in question will be water temperature.

The clearest example of how water temperature affects rise forms I've experienced was on a small mountain stream in Montana in 2018. My dad, my friend David Gallipoli, and I were fishing for native Yellowstone cutthroat trout with dry flies. The morning started out below freezing. Though my instinct was not to fish dries with the water and air so cold, David insisted these fish would come up. I tied on a dry dropper rig with a big Chernobyl ant as the top fly. It was almost shocking how quickly a cutthroat came up for the ant. And by quickly, I don’t mean it rose fast. Far from it. That fish took on my fourth cast in the pool, but rose and ate at an incredibly sluggish pace. The next couple fish did the same thing. But as the day progressed the sun worked its magic and the temperature climbed more and more. A funny thing happened… the fish didn’t seem to get any more willing to eat the Chernobyl as my catch rate remained the same, but they did take it with more gusto the warmer it got. It was fascinating. Towards the end of the outing the fish were flying off the bottom for the fly. The contrast with those sluggish rises early on was extraordinary. Then a BWO hatch started and the fish changed their behavior entirely, but that’s a different story.

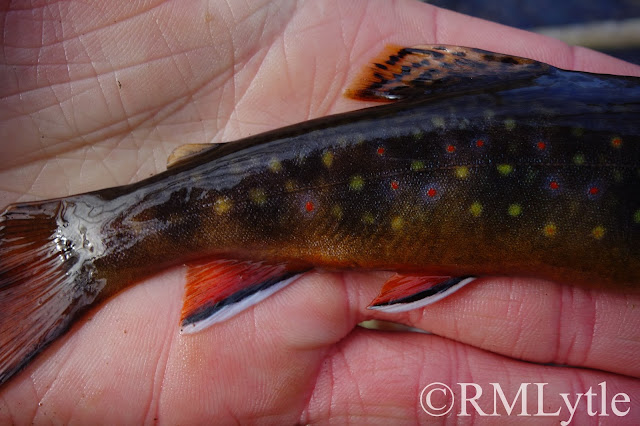

Flash forward to a mild January day in the first week of 2021. I was on a small meandering Connecticut brook trout stream. The water was cold, not even 40 degrees fahrenheit, and yet I had an Ausable Bomber tied on. I fully expected to bring up numerous wild brook trout, but I was not likely to see the sort of manic slashing takes I could expect in spring and early summer. Though this was a big bushy fly and the fish would certainly come up for it, I knew they’d be doing so very slowly. And that’s exactly what happened. I rose more than a dozen brookies, and they all came up slowly and gulped the fly very daintily.

Rise forms often dictate how we trout fish. Fly selection, presentation, hook set timing, and more can all be deciphered by how the fish are rising. Fly selection and presentation can also sometimes dictate the rise form if fish are actually willing to eat your offering. A skated fly amongst fish sipping emergers might get smashed by a more aggressive trout. But in the winter the rise will almost always be slow, even if you’re fishing a big ass chernobyl ant or skating a bomber, so don’t let seeing only subtle dimples for natural bugs dissuade you from swinging a big dry through a riffle every now and then.

No comments:

Post a Comment